Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

A critical part of delivering high availability is ensuring that services can survive all different types of failures. This is especially important for failures that are unplanned and outside your control.

This article describes some common failure modes that might be disasters if not modeled and managed correctly. It also discusses mitigations and actions to take if a disaster happens anyway. The goal is to limit or eliminate the risk of downtime or data loss when failures, planned or otherwise, occur.

Avoiding disaster

The main goal of Azure Service Fabric is to help you model both your environment and your services in such a way that common failure types are not disasters.

In general, there are two types of disaster/failure scenarios:

- Hardware and software faults

- Operational faults

Hardware and software faults

Hardware and software faults are unpredictable. The easiest way to survive faults is running more copies of the service across hardware or software fault boundaries.

For example, if your service is running on only one machine, the failure of that one machine is a disaster for that service. The simple way to avoid this disaster is to ensure that the service is running on multiple machines. Testing is also necessary to ensure that the failure of one machine doesn't disrupt the running service. Capacity planning ensures that a replacement instance can be created elsewhere and that reduction in capacity doesn't overload the remaining services.

The same pattern works regardless of what you're trying to avoid the failure of. For example, if you're concerned about the failure of a SAN, you run across multiple SANs. If you're concerned about the loss of a rack of servers, you run across multiple racks. If you're worried about the loss of datacenters, your service should run across multiple Azure regions, across multiple Azure Availability Zones, or across your own datacenters.

When a service is spanned across multiple physical instances (machines, racks, datacenters, regions), you're still subject to some types of simultaneous failures. But single and even multiple failures of a particular type (for example, a single virtual machine or network link failing) are automatically handled and so are no longer a "disaster."

Service Fabric provides mechanisms for expanding the cluster and handles bringing failed nodes and services back. Service Fabric also allows running many instances of your services to prevent unplanned failures from turning into real disasters.

There might be reasons why running a deployment large enough to span failures is not feasible. For example, it might take more hardware resources than you're willing to pay for relative to the chance of failure. When you're dealing with distributed applications, additional communication hops or state replication costs across geographic distances might cause unacceptable latency. Where this line is drawn differs for each application.

For software faults specifically, the fault might be in the service that you're trying to scale. In this case, more copies don't prevent the disaster, because the failure condition is correlated across all the instances.

Operational faults

Even if your service is spanned across the globe with many redundancies, it can still experience disastrous events. For example, someone might accidentally reconfigure the DNS name for the service, or delete it outright.

As an example, let's say you had a stateful Service Fabric service, and someone deleted that service accidentally. Unless there's some other mitigation, that service and all of the state that it had are now gone. These types of operational disasters ("oops") require different mitigations and steps for recovery than regular unplanned failures.

The best ways to avoid these types of operational faults are to:

- Restrict operational access to the environment.

- Strictly audit dangerous operations.

- Impose automation, prevent manual or out-of-band changes, and validate specific changes against the environment before enacting them.

- Ensure that destructive operations are "soft." Soft operations don't take effect immediately or can be undone within a time window.

Service Fabric provides mechanisms to prevent operational faults, such as providing role-based access control for cluster operations. However, most of these operational faults require organizational efforts and other systems. Service Fabric does provide mechanisms for surviving operational faults, most notably backup and restore for stateful services.

Managing failures

The goal of Service Fabric is automatic management of failures. But to handle some types of failures, services must have additional code. Other types of failures should not be automatically addressed for safety and business continuity reasons.

Handling single failures

Single machines can fail for all sorts of reasons. Sometimes it's hardware causes, like power supplies and network hardware failures. Other failures are in software. These include failures of the operating system and the service itself. Service Fabric automatically detects these types of failures, including cases where the machine becomes isolated from other machines because of network problems.

Regardless of the type of service, running a single instance results in downtime for that service if that single copy of the code fails for any reason.

To handle any single failure, the simplest thing you can do is ensure that your services run on more than one node by default. For stateless services, make sure that InstanceCount is greater than 1. For stateful services, the minimum recommendation is that TargetReplicaSetSize and MinReplicaSetSize are both set to 3. Running more copies of your service code ensures that your service can handle any single failure automatically.

Handling coordinated failures

Coordinated failures in a cluster can be due to either planned or unplanned infrastructure failures and changes, or planned software changes. Service Fabric models infrastructure zones that experience coordinated failures as fault domains. Areas that will experience coordinated software changes are modeled as upgrade domains. For more information about fault domains, upgrade domains, and cluster topology, see Describe a Service Fabric cluster by using Cluster Resource Manager.

By default, Service Fabric considers fault and upgrade domains when planning where your services should run. By default, Service Fabric tries to ensure that your services run across several fault and upgrade domains so that if planned or unplanned changes happen, your services remain available.

For example, let's say that failure of a power source causes all the machines on a rack to fail simultaneously. With multiple copies of the service running, the loss of many machines in fault domain failure turns into just another example of a single failure for a service. This is why managing fault and upgrade domains is critical to ensuring high availability of your services.

When you're running Service Fabric in Azure, fault domains and upgrade domains are managed automatically. In other environments, they might not be. If you're building your own clusters on-premises, be sure to map and plan your fault domain layout correctly.

Upgrade domains are useful for modeling areas where software will be upgraded at the same time. Because of this, upgrade domains also often define the boundaries where software is taken down during planned upgrades. Upgrades of both Service Fabric and your services follow the same model. For more information on rolling upgrades, upgrade domains, and the Service Fabric health model that helps prevent unintended changes from affecting the cluster and your service, see:

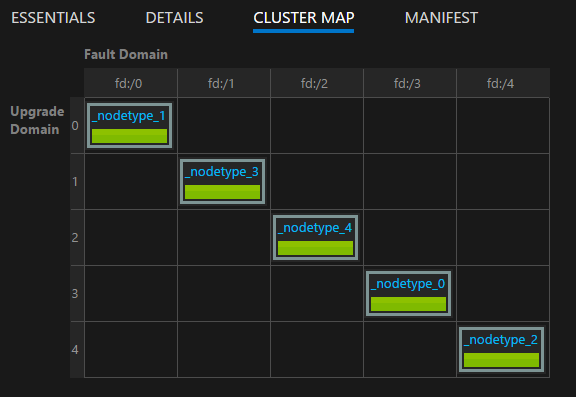

You can visualize the layout of your cluster by using the cluster map provided in Service Fabric Explorer:

Note

Modeling areas of failure, rolling upgrades, running many instances of your service code and state, placement rules to ensure that your services run across fault and upgrade domains, and built-in health monitoring are just some of the features that Service Fabric provides to keep normal operational issues and failures from turning into disasters.

Handling simultaneous hardware or software failures

We've been talking about single failures. As you can see, they're easy to handle for both stateless and stateful services just by keeping more copies of the code (and state) running across fault and upgrade domains.

Multiple simultaneous random failures can also happen. These are more likely to lead to downtime or an actual disaster.

Stateless services

The instance count for a stateless service indicates the desired number of instances that need to be running. When any (or all) of the instances fail, Service Fabric responds by automatically creating replacement instances on other nodes. Service Fabric continues to create replacements until the service is back to its desired instance count.

For example, assume that the stateless service has an InstanceCount value of -1. This value means that one instance should be running on each node in the cluster. If some of those instances fail, Service Fabric will detect that service is not in its desired state and will try to create the instances on the nodes where they're missing.

Stateful services

There are two types of stateful services:

- Stateful with persisted state.

- Stateful with non-persisted state. (State is stored in memory.)

Recovery from failure of a stateful service depends on the type of the stateful service, how many replicas the service had, and how many replicas failed.

In a stateful service, incoming data is replicated between replicas (the primary and any active secondaries). If a majority of the replicas receive the data, data is considered quorum committed. (For five replicas, three will be a quorum.) This means that at any point, there will be at least a quorum of replicas with the latest data. If replicas fail (say two out of five), we can use the quorum value to calculate if we can recover. (Because the remaining three out of five replicas are still up, it's guaranteed that at least one replica will have complete data.)

When a quorum of replicas fail, the partition is declared to be in a quorum loss state. Say a partition has five replicas, which means that at least three are guaranteed to have complete data. If a quorum (three out five) of replicas fail, Service Fabric can't determine if the remaining replicas (two out five) have enough data to restore the partition. In cases where Service Fabric detects quorum loss, its default behavior is to prevent additional writes to the partition, declare quorum loss, and wait for a quorum of replicas to be restored.

Determining whether a disaster occurred for a stateful service and then managing it follows three stages:

Determining if there has been quorum loss or not.

Quorum loss is declared when a majority of the replicas of a stateful service are down at the same time.

Determining if the quorum loss is permanent or not.

Most of the time, failures are transient. Processes are restarted, nodes are restarted, virtual machines are relaunched, and network partitions heal. Sometimes, though, failures are permanent. Whether failures are permanent or not depends on whether the stateful service persists its state or whether it keeps it only in memory:

- For services without persisted state, a failure of a quorum or more of replicas results immediately in permanent quorum loss. When Service Fabric detects quorum loss in a stateful non-persistent service, it immediately proceeds to step 3 by declaring (potential) data loss. Proceeding to data loss makes sense because Service Fabric knows that there's no point in waiting for the replicas to come back. Even if they recover, the data will be lost because of the non-persisted nature of the service.

- For stateful persistent services, a failure of a quorum or more of replicas causes Service Fabric to wait for the replicas to come back and restore the quorum. This results in a service outage for any writes to the affected partition (or "replica set") of the service. However, reads might still be possible with reduced consistency guarantees. The default amount of time that Service Fabric waits for the quorum to be restored is infinite, because proceeding is a (potential) data-loss event and carries other risks. This means that Service Fabric will not proceed to the next step unless an administrator takes action to declare data loss.

Determining if data is lost, and restoring from backups.

If quorum loss has been declared (either automatically or through administrative action), Service Fabric and the services move on to determining if data was actually lost. At this point, Service Fabric also knows that the other replicas aren't coming back. That was the decision made when we stopped waiting for the quorum loss to resolve itself. The best course of action for the service is usually to freeze and wait for specific administrative intervention.

When Service Fabric calls the

OnDataLossAsyncmethod, it's always because of suspected data loss. Service Fabric ensures that this call is delivered to the best remaining replica. This is whichever replica has made the most progress.The reason we always say suspected data loss is that it's possible that the remaining replica has all the same state as the primary did when quorum was lost. However, without that state to compare it to, there's no good way for Service Fabric or operators to know for sure.

So what does a typical implementation of the

OnDataLossAsyncmethod do?The implementation logs that

OnDataLossAsynchas been triggered, and it fires off any necessary administrative alerts.Usually, the implementation pauses and waits for further decisions and manual actions to be taken. This is because even if backups are available, they might need to be prepared.

For example, if two different services coordinate information, those backups might need to be modified to ensure that after the restore happens, the information that those two services care about is consistent.

Often there's some other telemetry or exhaust from the service. This metadata might be contained in other services or in logs. This information can be used as needed to determine if there were any calls received and processed at the primary that were not present in the backup or replicated to this particular replica. These calls might need to be replayed or added to the backup before restoration is feasible.

The implementation compares the remaining replica's state to that contained in any available backups. If you're using Service Fabric reliable collections, there are tools and processes available for doing so. The goal is to see if the state within the replica is sufficient, and to see what the backup might be missing.

After the comparison is done, and after the restore is completed (if necessary), the service code should return true if any state changes were made. If the replica determined that it was the best available copy of the state and made no changes, the code returns false.

A value of true indicates that any other remaining replicas might now be inconsistent with this one. They will be dropped and rebuilt from this replica. A value of false indicates that no state changes were made, so the other replicas can keep what they have.

It's critically important that service authors practice potential data-loss and failure scenarios before services are deployed in production. To protect against the possibility of data loss, it's important to periodically back up the state of any of your stateful services to a geo-redundant store.

You must also ensure that you have the ability to restore the state. Because backups of many different services are taken at different times, you need to ensure that after a restore, your services have a consistent view of each other.

For example, consider a situation where one service generates a number and stores it, and then sends it to another service that also stores it. After a restore, you might discover that the second service has the number but the first does not, because its backup didn't include that operation.

If you find out that the remaining replicas are insufficient to continue in a data-loss scenario, and you can't reconstruct the service state from telemetry or exhaust, the frequency of your backups determines your best possible recovery point objective (RPO). Service Fabric provides many tools for testing various failure scenarios, including permanent quorum and data loss that requires restoration from a backup. These scenarios are included as a part of the testability tools in Service Fabric, managed by the Fault Analysis Service. For more information on those tools and patterns, see Introduction to the Fault Analysis Service.

Note

System services can also suffer quorum loss. The impact is specific to the service in question. For instance, quorum loss in the naming service affects name resolution, whereas quorum loss in the Failover Manager service blocks new service creation and failovers.

The Service Fabric system services follow the same pattern as your services for state management, but we don't recommend that you try to move them out of quorum loss and into potential data loss. Instead, we recommend that you seek support to find a solution that's targeted to your situation. It's usually preferable to simply wait until the down replicas return.

Troubleshooting quorum loss

Replicas might be down intermittently because of a transient failure. Wait for some time as Service Fabric tries to bring them up. If replicas have been down for more than an expected duration, follow these troubleshooting actions:

- Replicas might be crashing. Check replica-level health reports and your application logs. Collect crash dumps and take necessary actions to recover.

- The replica process might have become unresponsive. Inspect your application logs to verify this. Collect process dumps and then stop the unresponsive process. Service Fabric will create a replacement process and will try to bring the replica back.

- Nodes that host the replicas might be down. Restart the underlying virtual machine to bring the nodes up.

Sometimes, it might not be possible to recover replicas. For example, the drives have failed or the machines physically aren't responding. In these cases, Service Fabric needs to be told not to wait for replica recovery.

Do not use these methods if potential data loss is unacceptable to bring the service online. In that case, all efforts should be made toward recovering physical machines.

The following actions might result in data loss. Check before you follow them.

Note

It's never safe to use these methods other than in a targeted way against specific partitions.

- Use the

Repair-ServiceFabricPartition -PartitionIdorSystem.Fabric.FabricClient.ClusterManagementClient.RecoverPartitionAsync(Guid partitionId)API. This API allows specifying the ID of the partition to move out of quorum loss and into potential data loss. - If your cluster encounters frequent failures that cause services to go into a quorum-loss state and potential data loss is acceptable, specifying an appropriate QuorumLossWaitDuration value can help your service automatically recover. Service Fabric will wait for the provided

QuorumLossWaitDurationvalue (default is infinite) before performing recovery. We don't recommend this method because it can cause unexpected data losses.

Availability of the Service Fabric cluster

In general, the Service Fabric cluster is a highly distributed environment with no single points of failure. A failure of any one node will not cause availability or reliability issues for the cluster, primarily because the Service Fabric system services follow the same guidelines provided earlier. That is, they always run with three or more replicas by default, and system services that are stateless run on all nodes.

The underlying Service Fabric networking and failure detection layers are fully distributed. Most system services can be rebuilt from metadata in the cluster, or know how to resynchronize their state from other places. The availability of the cluster can become compromised if system services get into quorum-loss situations like those described earlier. In these cases, you might not be able to perform certain operations on the cluster (like starting an upgrade or deploying new services), but the cluster itself is still up.

Services on a running cluster will keep running in these conditions unless they require writes to the system services to continue functioning. For example, if Failover Manager is in quorum loss, all services will continue to run. But any services that fail won't be able to automatically restart, because this requires the involvement of Failover Manager.

Failures of a datacenter or an Azure region

In rare cases, a physical datacenter can become temporarily unavailable from loss of power or network connectivity. In these cases, your Service Fabric clusters and services in that datacenter or Azure region will be unavailable. However, your data is preserved.

For clusters running in Azure, you can view updates on outages on the Azure status page. In the highly unlikely event that a physical datacenter is partially or fully destroyed, any Service Fabric clusters hosted there, or the services inside them, might be lost. This loss includes any state not backed up outside that datacenter or region.

There are several different strategies for surviving the permanent or sustained failure of a single datacenter or region:

Run separate Service Fabric clusters in multiple such regions, and use some mechanism for failover and failback between these environments. This sort of multiple-cluster active/active or active/passive model requires additional management and operations code. This model also requires coordination of backups from the services in one datacenter or region so that they're available in other datacenters or regions when one fails.

Run a single Service Fabric cluster that spans multiple datacenters. The minimum supported configuration for this strategy is three datacenters. For more, see Deploy a Service Fabric cluster across Availability Zones.

This model requires additional setup. However, the benefit is that failure of one datacenter is converted from a disaster into a normal failure. These failures can be handled by the mechanisms that work for clusters within a single region. Fault domains, upgrade domains, and Service Fabric placement rules ensure that workloads are distributed so that they tolerate normal failures.

For more information on policies that can help operate services in this type of cluster, see Placement policies for Service Fabric services.

Run a single Service Fabric cluster that spans multiple regions using the Standalone model. The recommended number of regions is three. See Create a standalone cluster for details on standalone Service Fabric setup.

Random failures that lead to cluster failures

Service Fabric has the concept of seed nodes. These are nodes that maintain the availability of the underlying cluster.

Seed nodes help to ensure that the cluster stays up by establishing leases with other nodes and serving as tiebreakers during certain kinds of failures. If random failures remove a majority of the seed nodes in the cluster and they're not brought back quickly, your cluster automatically shuts down. The cluster then fails.

In Azure, Service Fabric Resource Provider manages Service Fabric cluster configurations. By default, Resource Provider distributes seed nodes across fault and upgrade domains for the primary node type. If the primary node type is marked as Silver or Gold durability, when you remove a seed node (either by scaling in your primary node type or by manually removing it), the cluster will try to promote another non-seed node from the primary node type's available capacity. This attempt will fail if you have less available capacity than your cluster reliability level requires for your primary node type.

In both standalone Service Fabric clusters and Azure, the primary node type is the one that runs the seeds. When you're defining a primary node type, Service Fabric will automatically take advantage of the number of nodes provided by creating up to nine seed nodes and seven replicas of each system service. If a set of random failures takes out a majority of those replicas simultaneously, the system services will enter quorum loss. If a majority of the seed nodes are lost, the cluster will shut down soon after.

Next steps

- Learn how to simulate various failures by using the testability framework.

- Read other disaster-recovery and high-availability resources. Azure has published a large amount of guidance on these topics. Although some of these resources refer to specific techniques for use in other products, they contain many general best practices that you can apply in the Service Fabric context:

- Learn about Service Fabric support options.